A Critical Reimagining of the U.S.-Mexican Border Region

This project explores an architecture of borders. Borders are not merely abstract lines, but places with real people and real problems. Two artists who worked and lived across the contested border of Mexico and the U.S., Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe, have acted as creative muses to design a centre for women in the conurbation of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. The goal is to offer a critical reimagining of the border region, allowing women to gain protection and autonomy in a place where their lives is threatened daily. In its essence, the project consists of a garden with multiple communal facilities on the banks of the Rio Grande.

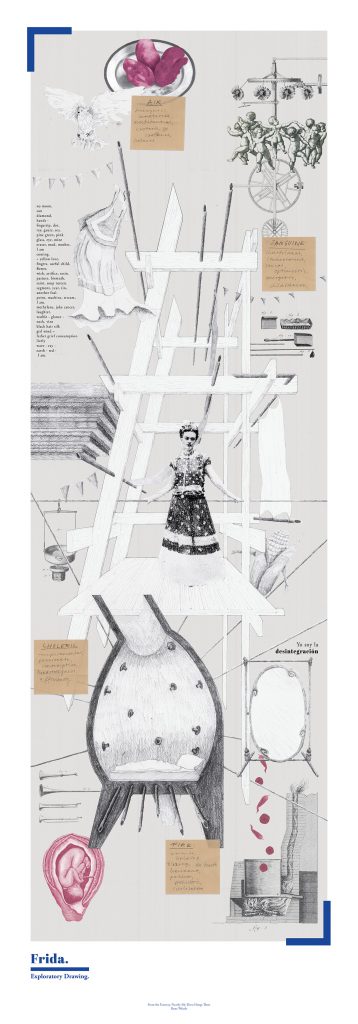

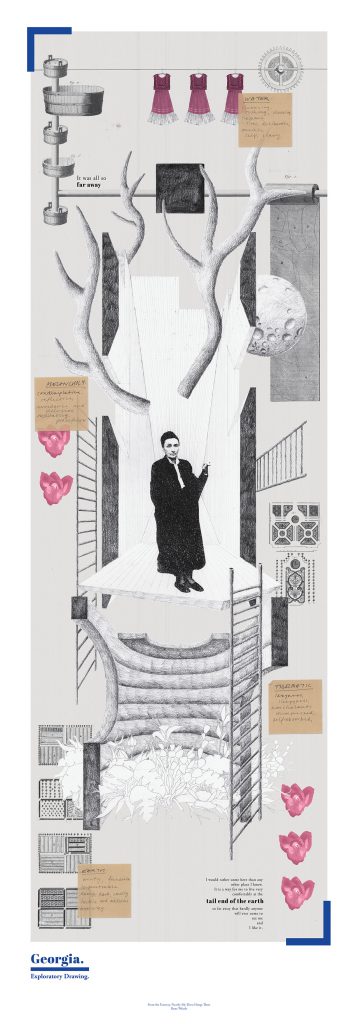

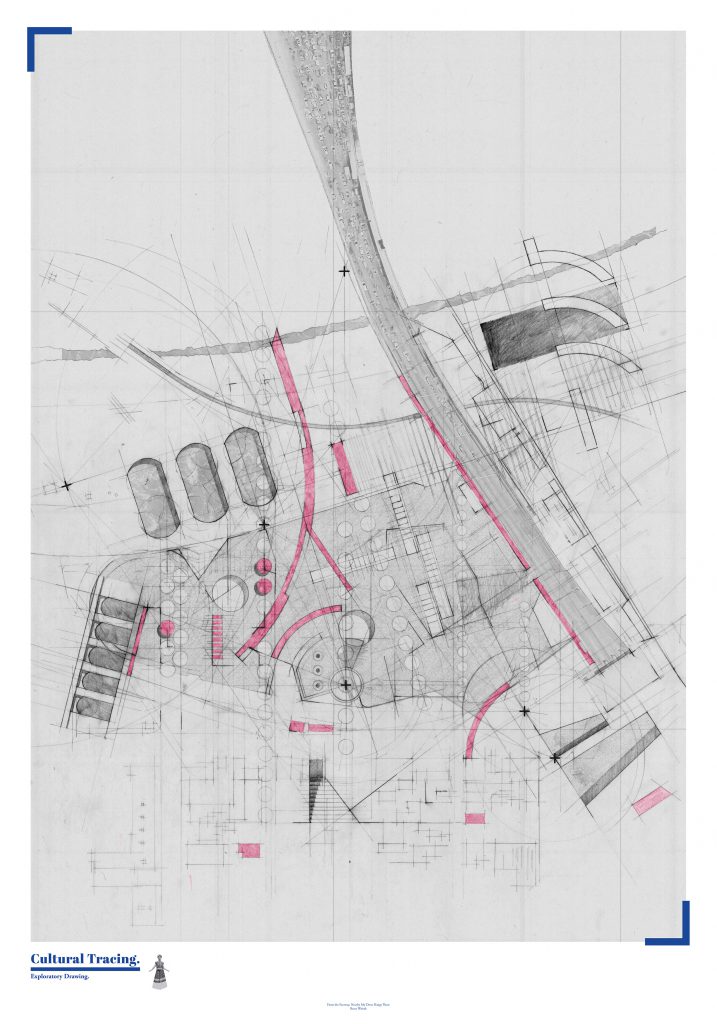

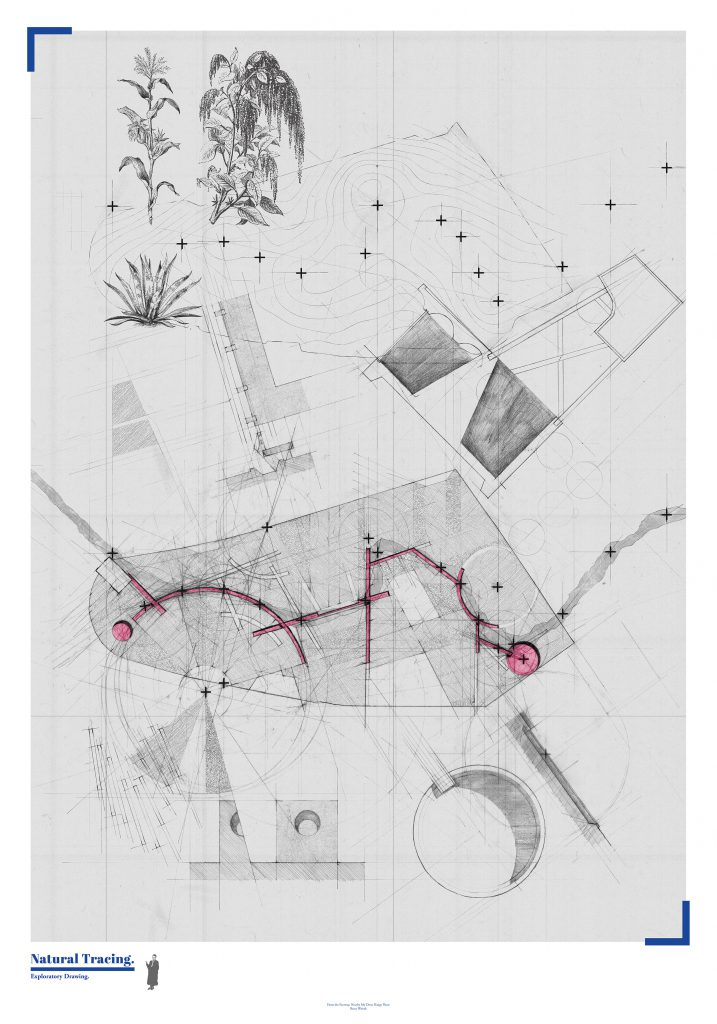

Pencil drawings/digital collages exploring the domestic space and place-making of Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo.

Across the border

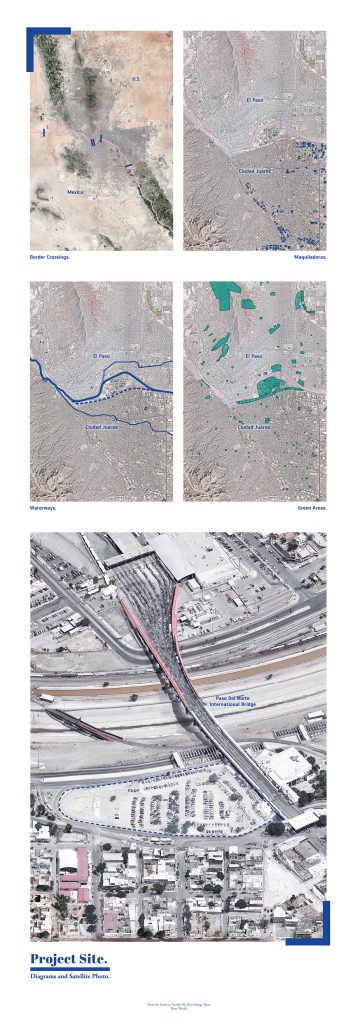

The U.S.-Mexican border is undeniably a politically contentious issue, and currently, the U.S. government does everything in its might to turn people around, especially after President Donald Trump took office. An increasing number of migrants from Latin American countries–many of them women and children–are fleeing climate disasters, oppressive dictatorships and, not least, domestic violence. This thesis project deals with one part of this complex whole: the conditions of the Mexican women adversely affected by the economic, political and societal structures of the border region. The problems are many: families are split apart, when husbands venture to the U.S. in search of work, leaving the women to care for the children; women work in slave-like conditions in the enormous maquiladoras, unable to find other employment; and, Juárez has one of the highest rates of femicides of any city in the world.

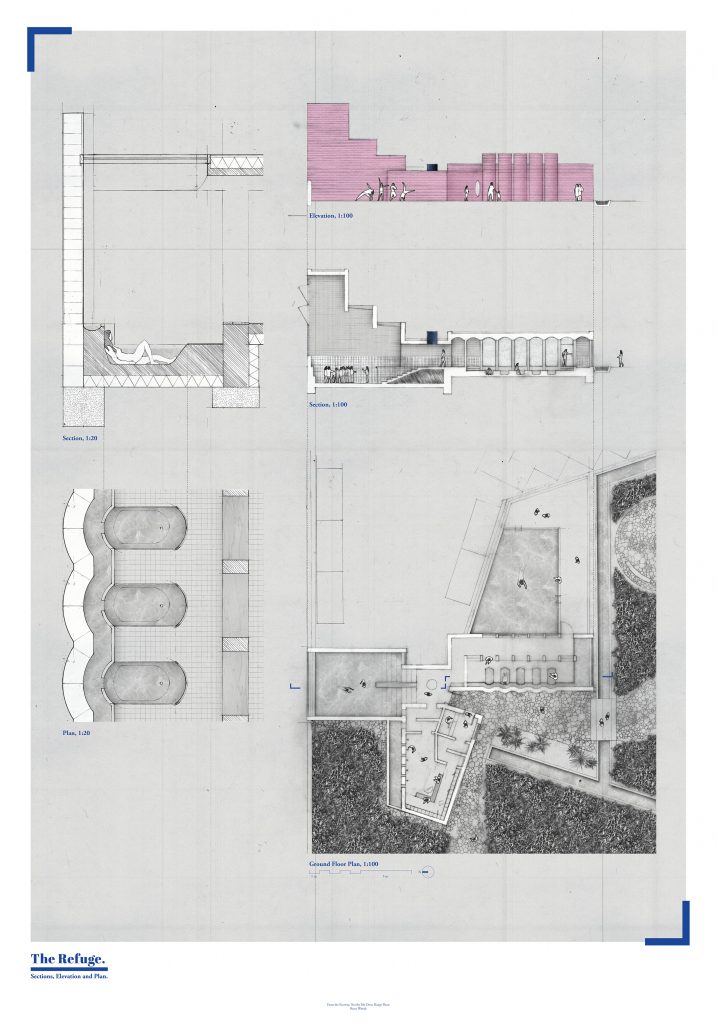

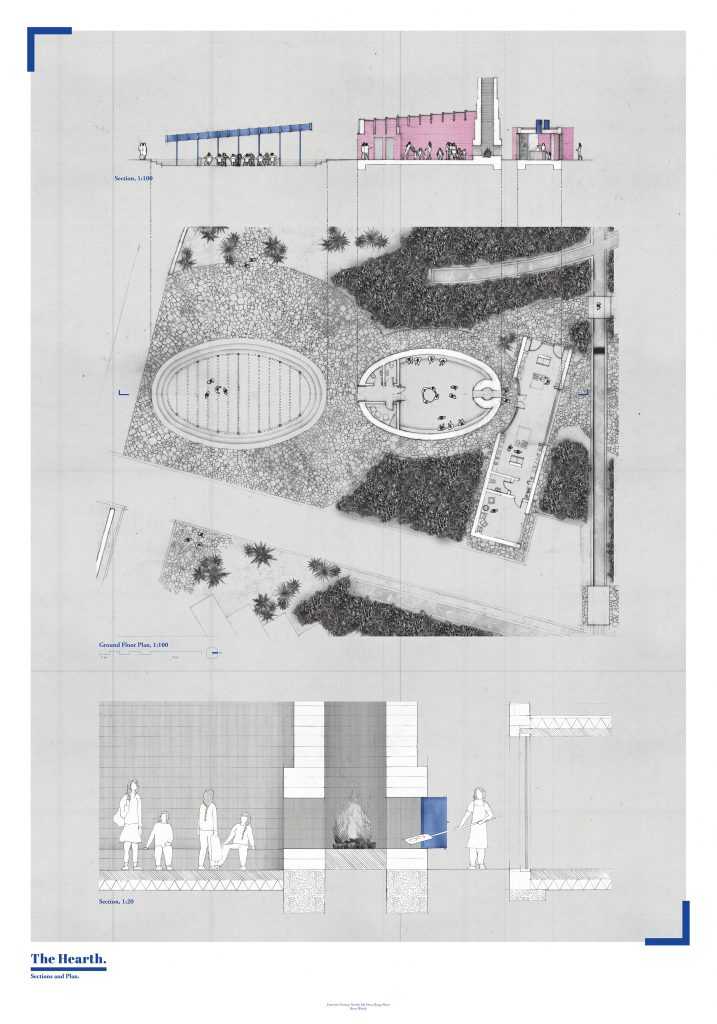

I believe that architecture can provide the community, the shelter and the sanctuary that is urgently needed. The heterotopic nature of the garden points not just at the immediate needs of the women, but also at their spirits, their enjoyment, their dreams. The hedonistic reimagining of domestic actions such as cooking, bathing and childcare remove these from the realm of sexism and reintroduce them in a new feminist reality.

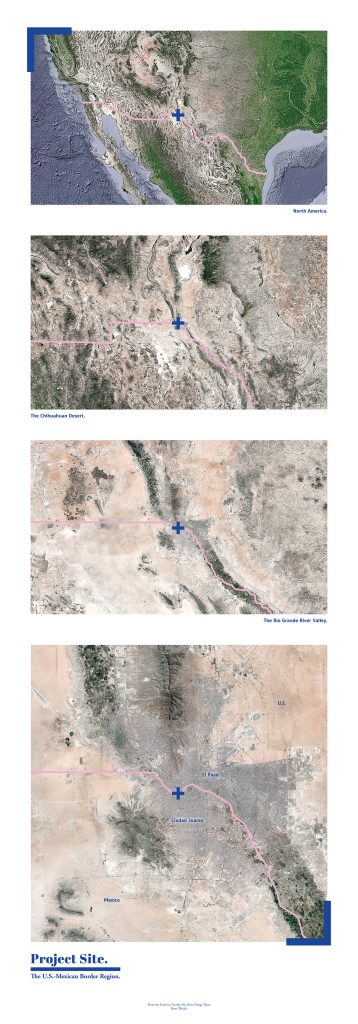

El Paso and Ciudad Juárez are situated in the middle of the North American continent. To the east, the border follows the Rio Grande – to the west, it cuts an arbitrary line through the desert.

The Twinned Cities

Straddled across the Rio Grande in the middle of the North American continent, El Paso del Norte has always been a significant crossing point. Since the times of Spanish conquest, it jas served served as a key point along the trade routes going West to the Pacific Ocean. Today, the conurbation of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez – the city on the Mexican side of the river–is an industrial powerhouse, with many residents crossing the border daily for work, school or even just shopping. But the tale of these two cities is a dichotomic one, born from the line that separates them.

Ciudad Juárez (est. 1.5 million inhabitants in 2019) is shorter of almost everything than El Paso (683,577 inhabitants in 2017 census). Sewers, houses, cars, electric lighting, money, calories per person, longevity – the smaller city sustains the larger. On average, about 23,000 people legally cross the border every day – and that’s only counting the pedestrians – many more cross by car or truck, but it can take as long as four or five hours of waiting in line to cross the border. Most of these people live, work and shop in both Mexico and the U.S., and many have dual citizenship.

For many years, Juárez has claimed the dubious honour of being one of the most violent cities in the world, with the murder rate soaring because of gang-related killings. But a stone’s throw away, tranquil El Paso has been on the list of ‘the top 10 safest cities in America’ for many years. Sadly, the recent shooting at a Walmart in El Paso has robbed the city of its title, the mass-murder tragically exemplifying the polarised situation at the border. In Juárez, murders are overwhelmingly committed against young women, attackers frequently seizing the victims on empty streets as they leave school or work.

This thesis project seeks to compliment and enhance the already existing infrastructure of the feminist organisations, the municipal efforts to promote women’s rights, and other services such as health clinics, schools and kindergartens. By focusing not just on the immediate and bodily needs of the women, but also on their spirits, their enjoyment, their dreams, this project will bring to light an ephemeral aspect of feminism that is often overlooked – the soul.

Design Methodology

The project methodology takes inspiration from the two artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo, who painted the natural and cultural phenomena of their respective countries, the U.S. and Mexico. There are great similarities between the two, but their artistic oeuvre is rooted in very different cultures and traditions, each with their unique perception of their land, their country. Furthermore, both artists have (posthumously in the case of Kahlo) become feminist icons, fighting for the right to live their own lives free from the preconceived gender norms inherent to large parts of North American society.

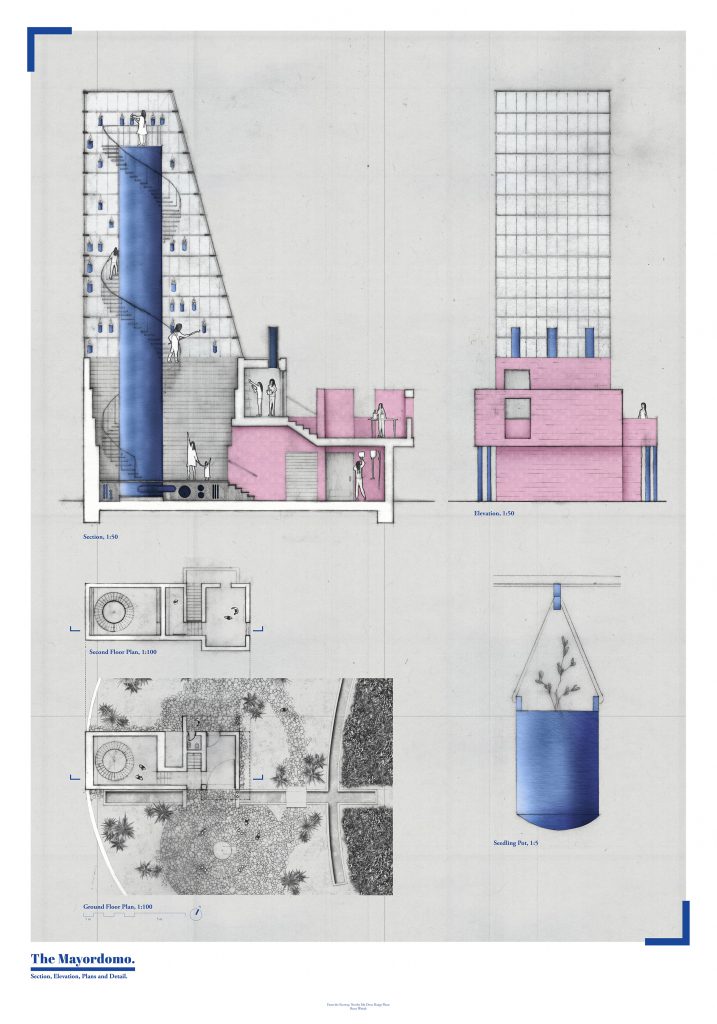

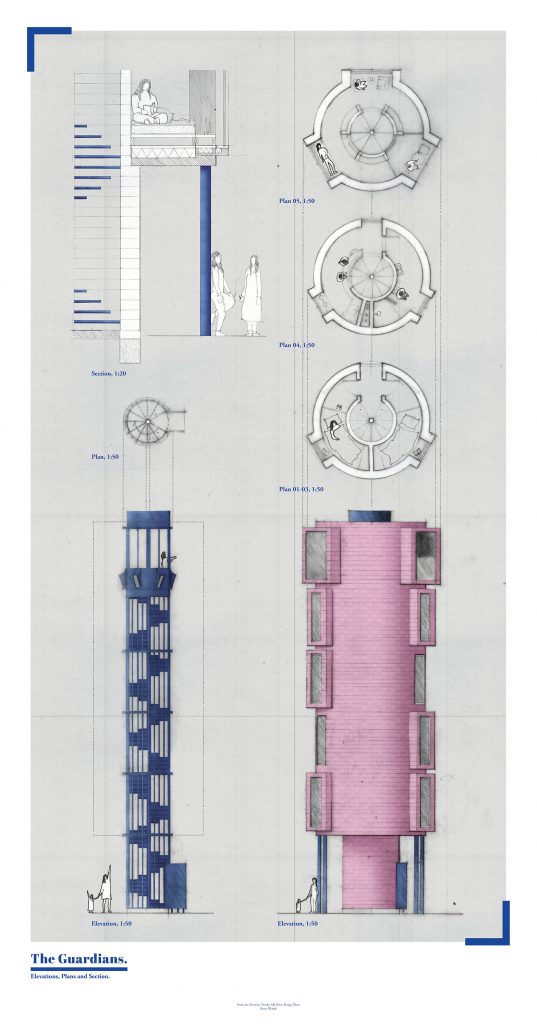

A formal, spatial and biographical analysis of the paintings From the Faraway, Nearby and My Dress Hangs There offers two distinct methods of constructing place: O’Keeffe presents abstractions of natural elements and conditions, while Kahlo collages together a myriad of cultural symbols that form the essence of a place. These two approaches become the method to design an architecture that interprets, stages and amplifies mundane natural and cultural elements already co-existing at the border. In this way, the project points not only to the basic and urgent needs of the women of the region, but seeks to introduce spirituality, joyfulness, community and dreaming.

The Pink Garden

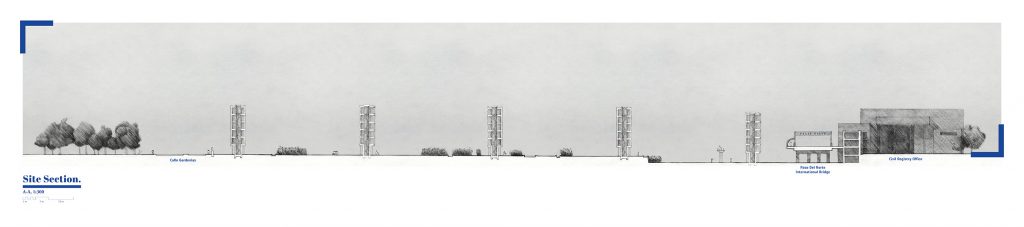

The project consists of a centre for women, which will form part of a strategy to grant women protection and autonomy in the community of Ciudad Juárez. The centre is established on the site of an existing parking lot near the Paso Del Norte International Bridge, one of the main thoroughfares across the border. This proximity facilitates the women commuting to El Paso, thus creating a possibility for higher income, better working hours and safer passage to and from work.

Through working with the artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo, the program of the project became a garden with multiple communal facilities, each of them a hedonistic interpretation of a quotidian domestic action: a place for cooking and meeting around the fire; a place for tending to the plants of the garden; and a place for pleasurable bathing and communal singing.

Ultimately, a border is not just a boundary between two nations, but a place in and of itself. It can be the source of severe political tension, but also the catalyst for cultural cross-fertilisation. We must reimagine the physical reality of the border, acknowledging the impact that architectural manifestations of checkpoints, bridges and walls have on the experience of place. By changing our understanding of the border region, we can go beyond national legislation and political divisions, opening a field for architects to act–and to create lasting social change.